Research Information is only available to members, click here to join

-

Research is central to everything that ACUR does.

-

It is one of ACUR’s core values. ACUR values the transformative power of research in all its forms as a vehicle for individual and collective learning. ACUR respects a diversity of approaches to undergraduate research engagement in line with the needs and requirements of universities and in support of their varied missions.

-

It is a foundational activity. Research was the basis for the establishment of ACUR and has been a constant driving force in its decision-making and development. This includes published research on teaching and research links, undergraduate research programs, decision-making and curriculum development, research on teaching spaces and the visibility of undergraduate research, academic identity, and social support in postgraduate research.

-

Research for ACUR is an aspiration. Research is a process of learning. It is the source of much of our understanding of the modern world. It has the capacity to enable us to grow in the face of uncertainty. Through engaging in research, we learn to cope with complexity and ambiguity. Research requires us to make sense of new phenomena and in doing so we develop the capacity to distinguish types of evidence, form rational judgements, and communicate what we have found.

-

Members of the Executive and Others are encouraged to establish research projects focused on the nature of undergraduate research and how to develop it. To this aim, ACUR works collaboratively with member institutions on joint research projects e.g. Honours. The Research Directorate provides support to project leaders in ethics applications, data gathering, publishing papers, and negotiating with university partners, e.g. honours projects. It is responsible for keeping track of this work, ensuring timely completion of projects, and encouraging appropriate dissemination of project outcomes. Members of the Research Directorate normally have a track record in research achievements and/or are academics and students actively involved in research or research administration.

Click on the buttons below

Did you know?

.

.

.

Academics’ define research in different ways

Here’s how ACUR defines it:

An inquiry or investigation or a research-based activity conducted by an undergraduate student that makes an original intellectual or creative contribution to the discipline and/or to understanding. (Brew, 2010 following Beckman & Hensel, 2009, p.40).

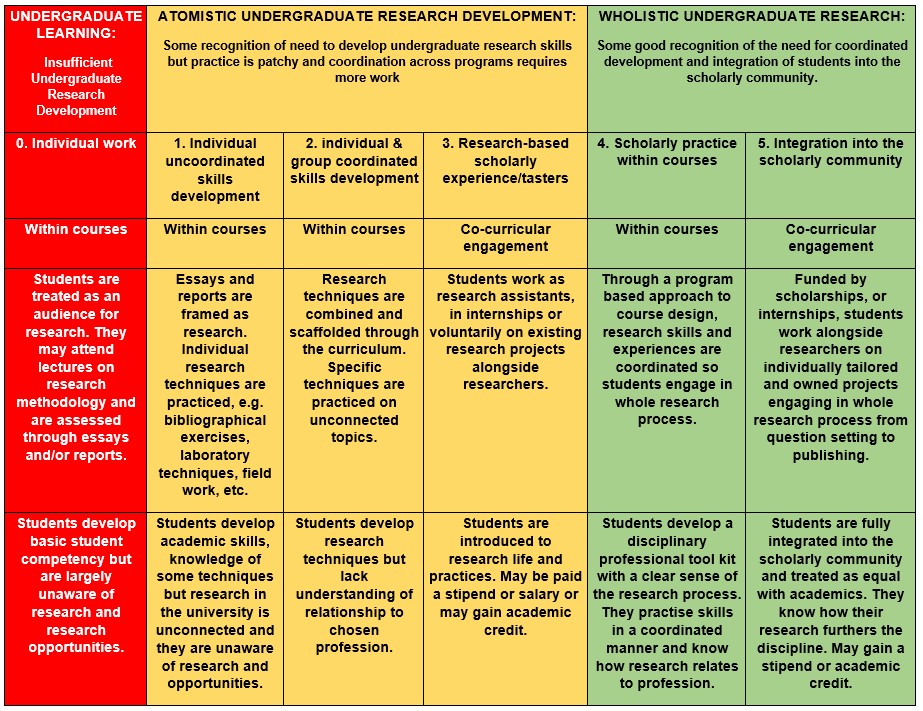

This broad definition masks considerable variation. In a study exploring the challenges and barriers to implementing research-based experiences for students, we asked academics how they would define undergraduate research. We found that there were differences in what academics thought undergraduate research was and who was able to do it. These are summarised in the following table.

| Span | Everything all students do | A specialised process only for a few students | |

| Guidance | Guided research (groups or individually) | vs…… | Independent research (groups or individually) |

| Process | Involvement in stages of research separately e.g. data collection | vs | Involvement in complete research process/trajectory e.g. question to write up/presentation |

| Focus | Developing skills (doing) | vs | Developing the student (being) |

| Quality | URG is secondary, lower quality research – not publishable | vs | URG is original publishable research generating new knowlege |

| Scope | UGR is for the student cohort and for the degree only | vs | Students treated as part of the research community/ know they have a wider role as a future researcher. |

The different definitions of undergraduate research given by academics in this study appeared to lead to different forms of undergraduate research being implemented. Some definitions appeared to open up opportunities for development while others appeared to limit it. These differing ways of thinking about undergraduate research affect which students are targeted, what year levels, the aims and scope of undergraduate research engagements, and the nature of the research learning. Indeed, they influence whether undergraduate research can be furthered at all.

.

Forms of Engagement in Undergraduate Research

If we’re keen to extend the research opportunities for students, then we need to recognise that our ideas about what undergraduate research is and who should be engaged in it are key to what options for development we might consider. With this in mind, we mapped examples of practice mentioned in our study, taking account of these differing definitions. This resulted in what we like to refer to as the “Traffic lights diagram”. Traffic light colours are used to differentiate three levels of engagement:

-

undergraduate learning;

-

atomistic approaches to undergraduate research development; and

-

wholistic undergraduate research.

After the diagram, we outline the main points of each form of engagement. For a fuller discussion see Brew & Mantai, (2017).

0 – Undergraduate learning

“Every time [students] read a book and they are thinking about a question they are actually researching. So research is an activity that happens every hour of every day in universities … It’s a way of thinking.” (10, p.4 Psychology, F, A/Prof)

While this may very well be true, the problem with this kind of thinking is that it can lead to students being largely unaware of research and research opportunities, as the literature has shown (see for example, Turner, Wuetherick & Healey, 2008). For this reason we do not think this can be counted as “undergraduate research”.

1 – Individual work, study and uncoordinated skills development

In this first true form of undergraduate research, essays and reports are framed as research and linked to journal article writing. Students carry out bibliographical exercises and/or critical literature reviews and they practice individual research techniques, e.g. laboratory techniques, data mining, field work, questionnaire design, etc. Students develop skills of academic writing and critical analysis. They develop knowledge of particular disciplinary techniques.

This form of engagement differs from the previous one in that an explicit link is made here between activities and research. UGR is conceptualised as something all students do, but it is not everything they do. Although activities may appear unconnected with research in the university and professions, and students may be largely unaware of research and research opportunities, some attempt is made here to link to research activities, e.g. writing academic articles.

2 – Coordinated skills development through individual and group work

In the second form, research techniques are combined and scaffolded throughout the curriculum. Students are involved in the different stages of research. They learn how to set hypotheses, generate questions, collect data, write reports, and engage in disciplinary techniques etc., but these may be practiced on unconnected topics. The focus is on research skills development, but students are unlikely to develop understanding of how the research they are doing relates to their chosen profession nor life afterwards.

3 – Research-based scholarly experience/tasters

Here students are involved in data collection or analysis in existing research projects working alongside staff, PhDs, post docs, etc. They may work as research assistants and/or as part of a scholarship scheme, or projects set up by academics. Students are typically paid a stipend or salary, or they may gain academic credit. Engagement may be voluntary. This form of engagement is still atomistic because, although students are introduced to research life and practices of scholarly engagement, the work is unconnected to their learning in courses.

4 – Scholarly practice within courses

As we move to more wholistic undergraduate research, a program based approach to the design of courses can ensure students acquire a coordinated set of research skills and experiences. Students develop their disciplinary “professional tool kit”. Students devise questions or hypotheses, set up experiments, or carry out fieldwork to answer them, collect the data, analyse it and report on the findings. The curriculum structure enables them to gain a clear sense of the process of research in the discipline. They can practice skills needed and they know how research relates to their chosen profession and life afterwards. The focus is on developing the student as researcher.

5- Integration into the scholarly community

Opportunities for student to work alongside academics on individually tailored research projects were viewed by some academics in our study to be the only way undergraduate students can engage in research. Students in this conception engage in the whole process. They devise questions or hypotheses, set up experiments, carry out fieldwork, collect the data, analyse it and publish the findings. Engagement may be as summer or winter vacation scholarships, or internships. Students are typically paid a stipend or may gain academic credit. They are fully integrated into the scholarly community, are treated as equals with academic researchers and have ownership of particular projects. They know how the research they are doing furthers the discipline. Their research generates new knowledge that is publishable.

..

.

What is Facilitative of Undergraduate Research Development: What works?

University policies, procedures and structures

University policies that encourage or provide a framework for undergraduate research are helpful. For example, do your new course proposals include research experiences and outcomes?

Publicise examples, maps, programs or outlines of what has been done already. Our quarterly newsletter URNA is a great outlet to publicise your work.

Develop a structure for scaffolding research within units.

Simplify ethics requirements for low-risk coursework research.

One idea is to have research-led teaching associate deans or directors in faculties so that they can integrate research and teaching strategy.

Facilitate structures for encouraging undergraduate research.

Include a program-based approach to course development.

Three- hour ‘lecture slots’, block seminars and the idea of the ‘flipped’ classroom all provide time for inquiry-based activities during class time.

Why not include an inquiry or a stimulating provocative question as part of induction in O-Week to set the tone for student learning and engage them in critical reflection from day 1?

Set up a cross-faculty/departmental working group on undergraduate research. This is useful in spreading ideas and showcasing possibilities.

Undergraduate research conferences are held in many universities and are great for encouraging initiatives in departments. Organise one if your university doesn’t already do this. Connect with ACUR for guidance or tell us about it.

A coordinated system for undergraduate research internship programs including a formal structure for applying for grants and a coordinated approach for the allocation of undergraduate scholars are also important.

Reward and recognise work that promotes undergraduate research. For example, if a course with some element of inquiry is counted as workload this encourages staff to engage. One university uses a ‘banking’ system whereby staff can ‘bank’ their work on undergraduate research, e.g. being a mentor to one student, running a research-based unit etc., They can draw down on their account for time off or research funding.

Student engagement

Provide opportunities for students to gain academic credit for undergraduate research.

Support student societies that focus on research such as the Biology Student Society (9, p.6), History Society, etc., and encourage students to set up an Undergraduate Research Student Society,

Actively encourage students’ attendance at undergraduate research conferences, especially ACUR.

Connect students with ACUR social media accounts (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and disseminate URNA newsletters.

Encourage students to ask their lecturers to include an inquiry component in their courses.

Develop a culture of undergraduate research and inquiry

Discussion amongst academics is a key facilitator in encouraging the spread of ideas about undergraduate research and inquiry. This can be sharing examples, talking to colleagues about what staff are doing, or what is possible, modelling good practice, and encouraging academics to put forward projects in funded schemes.

Provide opportunities for professional learning for academics and sessional staff including sharing good practice, encouraging discussion and providing resources to support this.

Challenge unhelpful understandings of undergraduate research.

Audit current practice using the forms of engagement and discuss progress through audit and review.

Provide one-to-one specific help working alongside staff, workshops and showcases, as well as have accessible resources for staff to develop staff confidence in knowing what they can do.

Provide resources for academics to fit undergraduate research into their own research programs. Encourage applications for research grants to include undergraduate scholars.

Develop a culture where undergraduate research, evidence-based practice, and research-based teaching and learning are seen as normal.

Employ course conveners who enjoy research, and who were formerly undergraduate researchers themselves (Tip: look for staff educated in the USA as they may well have personal experience of undergraduate research).

Having a supportive current or previous head of department or significant senior person also helps especially if there is a history of UGR implementation whether or not it is currently active.

Instigate a system of rewards for academics who integrate research into their courses. These might be financial or workload related.

Funding, even small amounts, is facilitative.

Provide opportunities for post docs and PhD students to mentor or co-mentor undergraduates in labs, research projects, and internships.

What have you found helpful in advancing undergraduate research? Please share in the InConversation forum.

.

.

What Inhibits Progress in Extending Undergraduate Research?

We’re already doing it

You could say this is one of the biggest stumbling-blocks to any academic development; there is no need to do anything because we are already doing it. The idea that students are doing research whenever they are studying, writing essays and reports, reading bibliographic material, etc., can become stuck in this mindset. This view needs to be challenged. Do students know how what they are doing relates to the research that their teachers are doing? How are the links with research practice being made? What are the actual skills that students are developing? Are they aware that they are developing research skills?

If everything students already do is considered to be research, then it will be assumed that the university’s aims in undergraduate research have already been met, and there is no need to do anything different. So this idea must be challenged.

Undergraduate students aren’t capable of doing research

It is noticeable that some definitions of undergraduate research are based upon preconceived ideas that students are incapable of research. Given that school children are recognised as being capable of doing (sometimes publishable) research (see e.g. Kellett, Forrest, Dent & Ward, 2005; Steinburg & Kincheloe, 1998) again these ideas need to be challenged. Indeed, opening up mindsets (both staff and students) to new possibilities is essential if universities are to achieve aspirations to develop undergraduate research.

For example, a range of opportunities for engaging in both guided research and independent research, involving students both in the stages of research and in the complete research process need to be fostered, possibly at different levels. It may be that atomistic undergraduate research development is appropriate in the early years (see Forms of engagement Nos. 1, 2 and 3 ). Students then may move to more wholistic development in third year; i.e. to forms of scholarly practice within courses (No. 4), with an increasing number of students gaining experience of integration into the scholarly community (No. 5).

Undergraduate research is lower-level research, not real research leading to new discoveries

There may be occasions when students are engaging in lower-level research in order to learn, and other occasions when they are engaging in generating new knowledge. And while there are times when a focus on skills is appropriate, ways need to be found to encourage researcherly attitudes and behaviours in students, and for them to know that these are relevant in whatever profession they undertake.

Any simple google search on “undergraduate research discoveries” will easily demonstrate undergraduates’ capacity to generate new knowledge! Here are some examples:

Undergraduate research is costly

It is true that integrating students into the scholarly community can be resource-intensive and only likely to be available to very few students. There is, after all, not enough room in the lab for all the students to do research So without extra resources, development at this level is limited. However, it is fair to say that undergraduate tax-free stipends are an excellent way for students to gain experience of working with an academic or with post-docs and Phd students in a lab. Alternatively, research-based learning within a unit or series of units can be accommodated within existing resources and can open up opportunities for all students to be engaged in some form of research and inquiry.

My research is too technical, too difficult, for undergraduates to understand

In workshops and talks, someone nearly always comes up with this, and I say. “Don’t’ think about the research that students can’t do/can’t contribute to, think of what they can do”. How many students in the class? Suppose you had that number of research assistants what would you be able to achieve? Have a look at “Ten Easy Ways” and see if there’s an idea you can adapt.

Most students don’t need to do research because they’re not going to become researchers

Doing research as an undergraduate is not just for those who are going to be researchers. Employers and professional bodies are demanding that students develop a range of research and inquiry skills. Work is increasingly enquiry based. Professions are increasingly enquiry-based. The demands of employers point to a research-based higher education. The kind of world we live in and the sort of professional life that students are going to have absolutely demands that they develop the kinds of skills that they will get through research-based experiences.

Students can’t do publishable research

There is a wealth of evidence that undergraduate students are capable of publishing their research. Not only are there numerous international journals available for student research to be published, but there is ample evidence of students contributing to highly regarded international peer reviewed journals in many disciplines.

For lists of undergraduate journals, go to:

Undergraduate Research in Australia – Useful websites – Macquarie University (mq.edu.au)

Also search on “Theme” “Undergraduate journals”

Have you come across something that is inhibiting undergraduate research?

Please share in the Discussion Forum.

.

Want to know more?

The ideas in this section are based on:

Brew, A., & Mantai, L. (2017). Academics’ perceptions of the challenges and barriers to implementing research-based experiences for undergraduates. Teaching in Higher Education. 22:5, 551-568 doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1273216.

See also:

Brew, A., & Saunders, C. (2020). Making sense of research-based learning in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education (87) 102935.

Hensel, N. (2012). Characteristics of excellence in undergraduate research (COEUR). Washington, DC: Council on Undergraduate Research. Available: ERIC – ED603274 – Characteristics of Excellence in Undergraduate Research, Online Submission, 2012 Accessed 24th November 2020.

Brew, A. (2013). Understanding the scope of undergraduate research: A framework for curricular and pedagogical decision-making. Higher Education. 66 (5) 603–618.

Check out the Resources section for a full annotated bibliography